I came up with a definition that night. It will sound familiar to those of you who are practitioners of Nonviolent Communication. Suffering, for me, is experienced through so-called ‘unpleasant’ emotions (anxiety, frustration, resentment, and more) and is essentially triggered by repetitive, negative thought patterns because underneath all that, there is a real experience of many needs being unmet as a result of the pain. Some that have been chronically unmet for me include freedom, play, contribution, relaxation, peace of mind, planning, social engagement and more.

I came up with a definition that night. It will sound familiar to those of you who are practitioners of Nonviolent Communication. Suffering, for me, is experienced through so-called ‘unpleasant’ emotions (anxiety, frustration, resentment, and more) and is essentially triggered by repetitive, negative thought patterns because underneath all that, there is a real experience of many needs being unmet as a result of the pain. Some that have been chronically unmet for me include freedom, play, contribution, relaxation, peace of mind, planning, social engagement and more. If we were encouraged at an early age to recognise and welcome our emotions, articulate them, link them to needs – met or unmet – and learn practices to develop resilience, we wouldn’t be suffering so much. When life meets us in unkind and unpleasant ways, we could be better resourced to face the intensity of emotions that arise in us, manage to face pain without wiggling like worms in panic and basically stay more relaxed and trustful within. We would even manage to recognise opportunities for growth in the most challenging situations.

If we were encouraged at an early age to recognise and welcome our emotions, articulate them, link them to needs – met or unmet – and learn practices to develop resilience, we wouldn’t be suffering so much. When life meets us in unkind and unpleasant ways, we could be better resourced to face the intensity of emotions that arise in us, manage to face pain without wiggling like worms in panic and basically stay more relaxed and trustful within. We would even manage to recognise opportunities for growth in the most challenging situations.

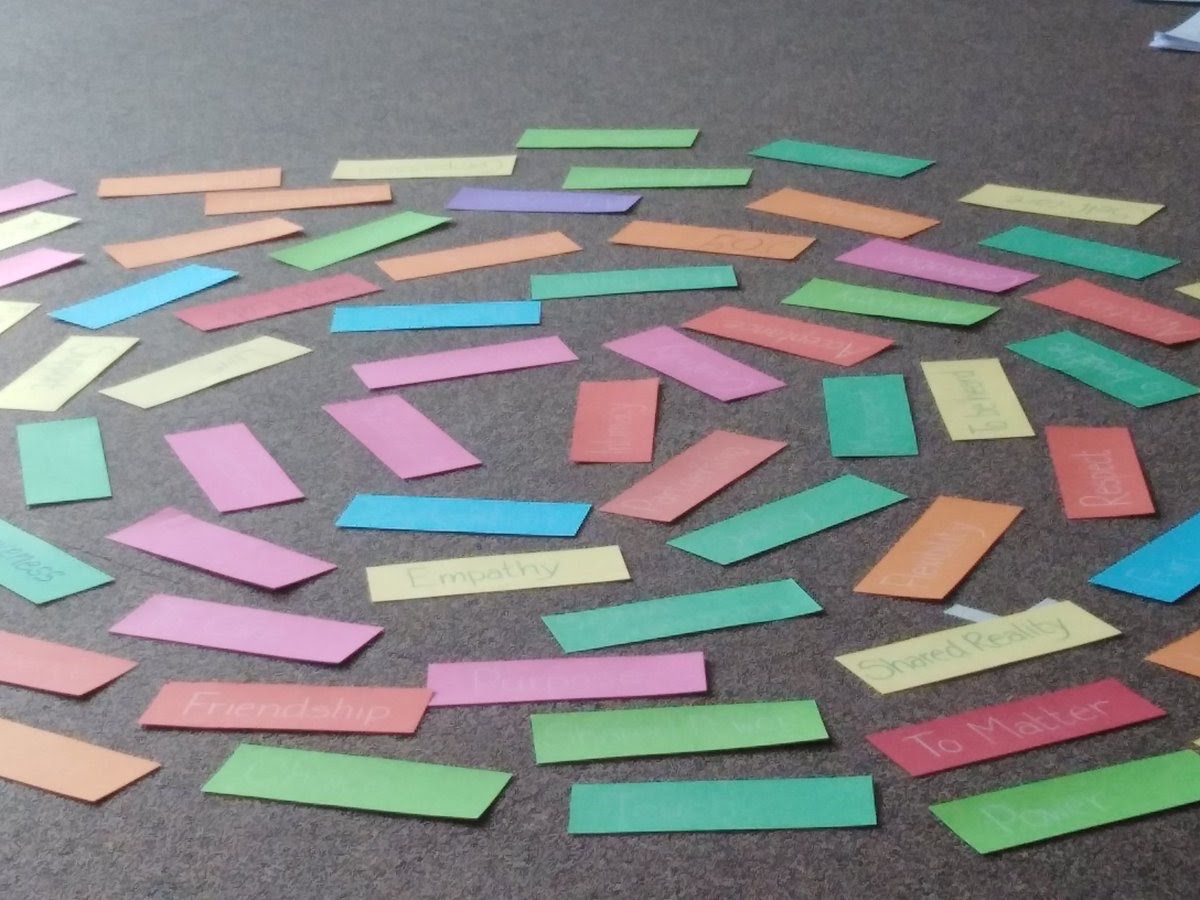

Instead, what most often happens is that we quickly get trapped into suffering, most vividly manifested by inescapable loops of anxious thoughts and it’s easy to fall into hopelessness. What causes this phenomenon, I believe, is that we are literally not allowed to feel. We haven’t got in us to stay with our feelings and embrace them, whatever their degree of intensity. More importantly, when feelings arise, the vast majority of us – including in many non-Western cultures -, feel alone with them because we know we won’t be met by others when we express them. Instead, our expression is received with discomfort, judgment, at best sympathy, but very rarely true empathy. The end result, at an individual level, is that most of us will do anything we can to avoid feeling the pain. As a result, we engage in a range of escaping and numbing strategies and we suffer. At a collective level, the numbness translates into sustaining systems that lead to unspeakable human suffering and the destruction of the planet.

Amongst a whole range of practices and support structures that have fed me along the way (see a previous blog here), teachings from wisdom traditions have helped me greatly to take some distance from my suffering. I want to name one such resource as it has been particularly soothing and transformative: the teachings of Jewish, Hindu spiritual teacher Ram Dass and in particular the book he co-wrote with his friend Mirabai Bush: “Walking Each Other Home: Conversations on Loving and Dying”. I’ll leave you with one quote:

Amongst a whole range of practices and support structures that have fed me along the way (see a previous blog here), teachings from wisdom traditions have helped me greatly to take some distance from my suffering. I want to name one such resource as it has been particularly soothing and transformative: the teachings of Jewish, Hindu spiritual teacher Ram Dass and in particular the book he co-wrote with his friend Mirabai Bush: “Walking Each Other Home: Conversations on Loving and Dying”. I’ll leave you with one quote: